The elderly are getting less and worse care. Seeing less of their family, feeling less useful, and slowly losing their relevance to society. What are we doing to take care of our elderly in the way we build and live?

Loneliness is a new pandemic. People are more alone and feel lonelier which is leading to an increase in anxiety and depression – which again is leading to more people not working, more people falling outside of society, and, worst case, more suicides. What do we need to do to combat increasing loneliness?

Another consequence of the loneliness pandemic is that there is a record amount of single people. A correlating statistic is that we are seeing fewer babies born than ever before. On top of this, the younger couples able to have babies are delaying it. Seeing how young people can’t afford proper housing, how could they afford having babies? What can we do about our younger generation not being able to afford proper housing?

Waiting lists for social housing is on the rise. The lack of social housing is making the municipality take to the private market and rent from there. The apartments are often the worst ones that no one else really wants, with poor living conditions. What can we change about social housing and it’s increasing waiting list?

Could we combine these challenged to help each other in a project? This is the theme of this diploma.

When our minister of health, Ingvild Kjerkhol, recently said that “we have to take care of our own old age” after we have seen a steady decline in both amount and quality of elderly care. Take care of our own old age. Make sure you can take care of yourself during the time which you become less and less able to take care of yourself. A juxtaposition in itself. The elderly rely more on help from others as they age. And as long as we see a decrease in available care and its quality, the help has to come from those around us. Family, friends, and neighbours have to step in for the health care workers.

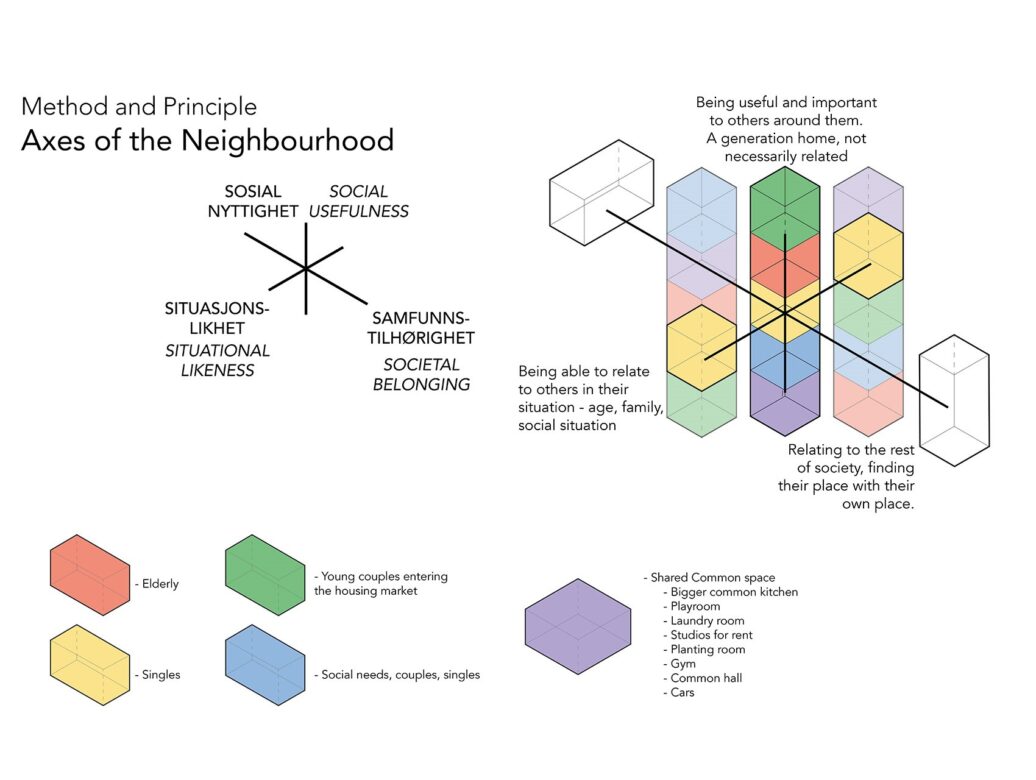

We are getting older, we are getting more lonely, and we are having less children. These problems scream for a solution. A common solution or method could be an introduction of a third housing sector. A housing sector between social/communal housing and the private own/rent sector. A housing sector where the municipality or government controls a part of the market. A sector where diversity is accepted and curated.

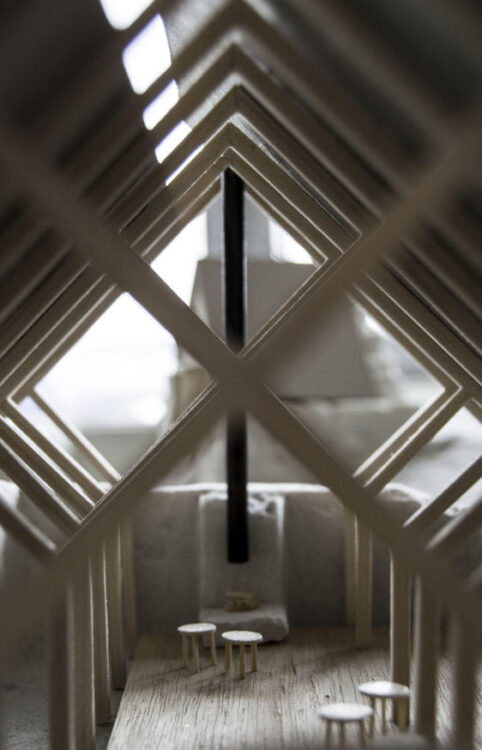

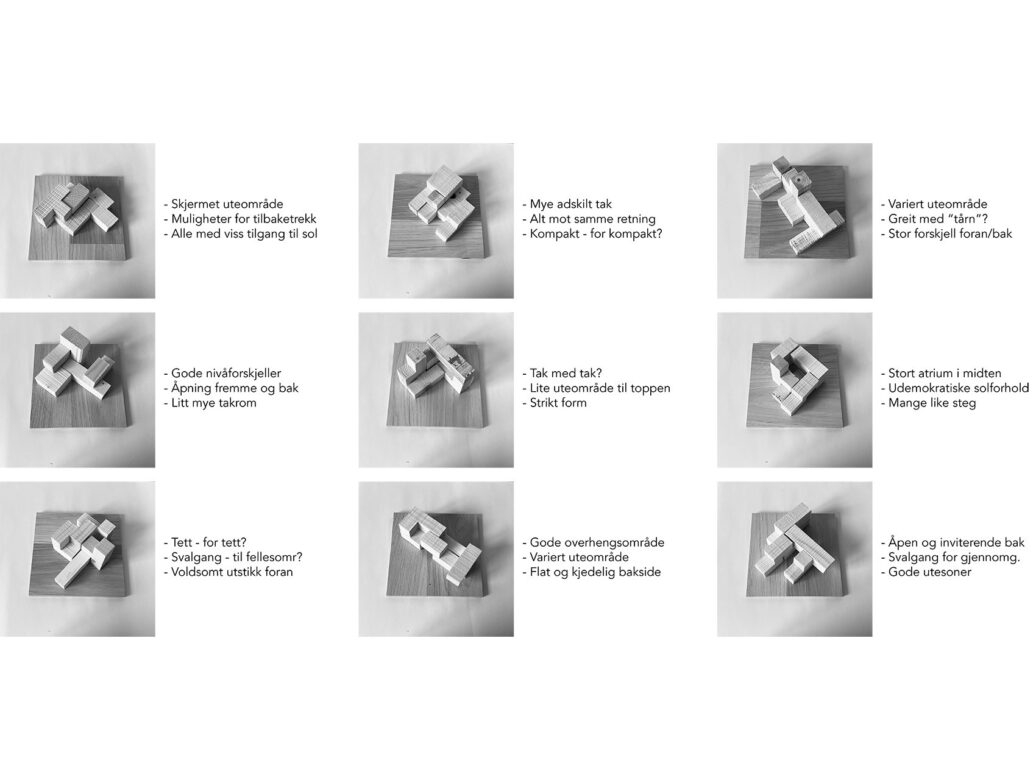

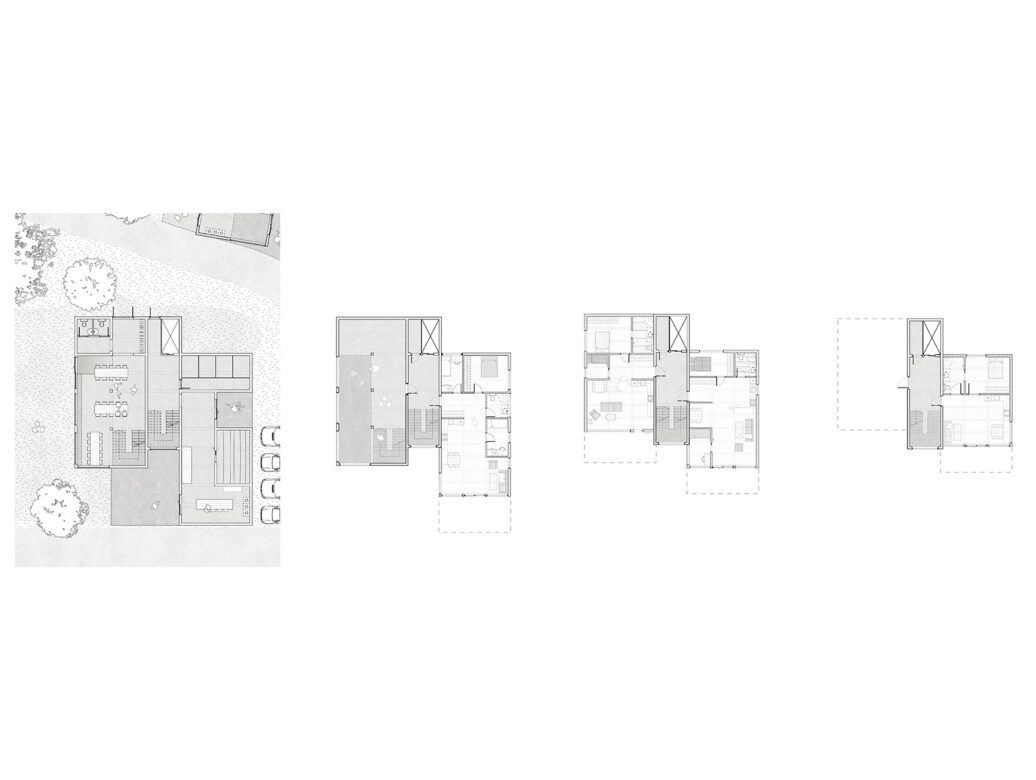

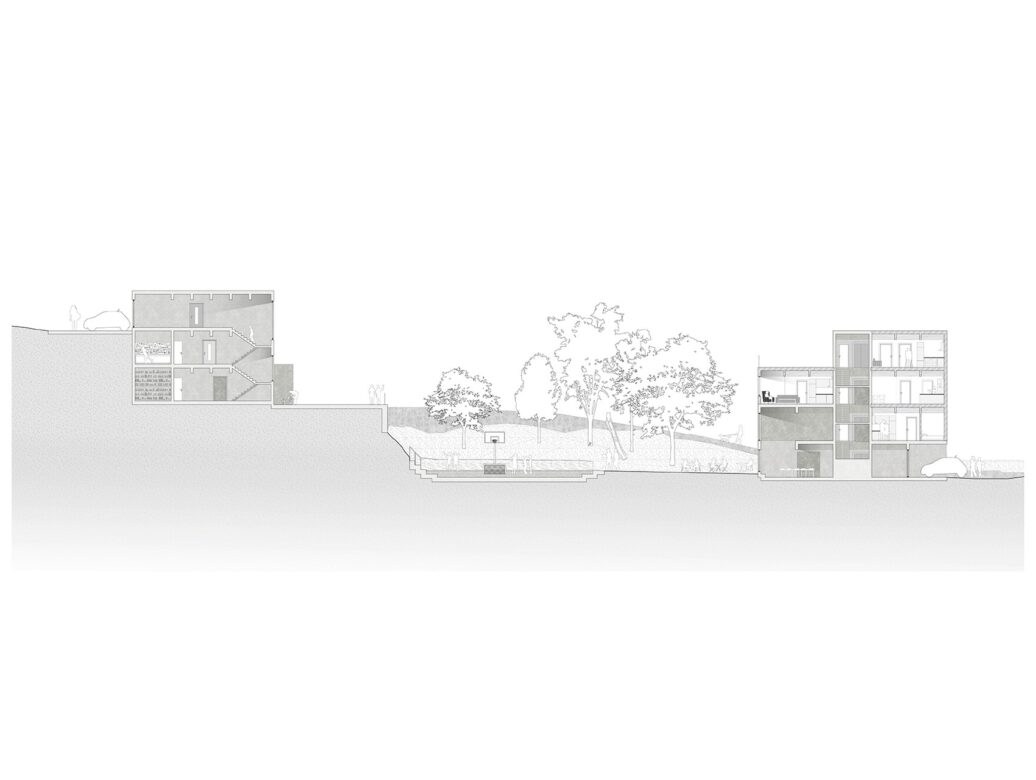

This diploma creates several “generational houses” in this sector. All consisting four units – one family unit, one special needs unit, one elderly unit, and one singles unit. Private diverse dwellings with a shared ground floor with several types of programmes to cater to their respective building, their closest neighbouring buildings, and the whole neighbourhood around them. By assuring literal common ground in the buildings it will allow for casual meetings between neighbours, a closer neighbourship, and help fight the loneliness.

If a couple not from the city buy a cheaper form of housing here, they could have “grandparents” and “uncle” in their building, who could babysit or help them fix their bike. The older residents would have some entertainment to watch, people around them, and would be able to get help in doing simpler tasks. There are possibilities for joint dinners, workshops, parties, planting etc. in the common rooms, as well as proper space in their own dwellings so they could retire to their own space.

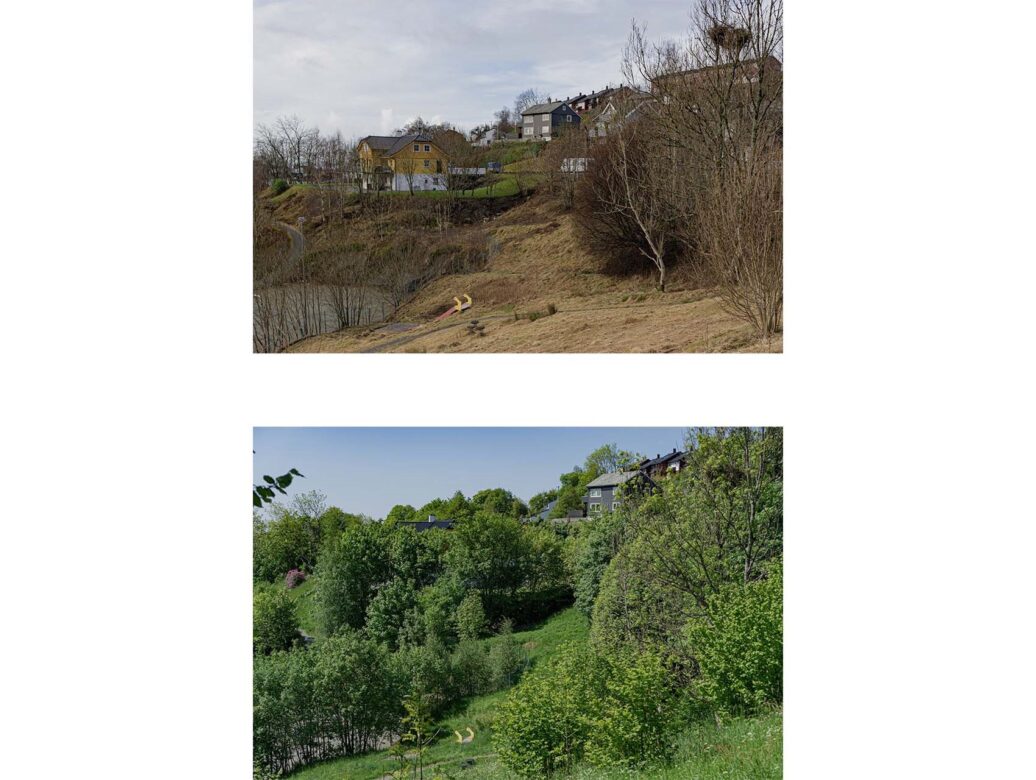

As a starting point for this method, I have found a plot in Sædal in Bergen. An open spot between villas and more recently developed apartments and family housing. An open area to try to create some middle and common ground between old and new, and be included in the neighbourhood. In the future, the project could buy housing from the private properties around it and include them in the project to send the ripples of neighbourship further. More smaller neighbourhoods using this method could emerge elsewhere in the city and country.