Due to hydropower, also salmon, a species long important to the region, went extinct. With salmon gone, many that depended on fishing, lost their livelihood, and the collective cultural traditions of salmon fishing faded. Hydropower construction provided short-term jobs for locals, but as the control of power plants was automated, the liveliness around the hydropower sites also soon declined.

Hydropower also changed the rhythm of the river. The river that used to change according to the seasons gradually answered now to the fastchanging electricity consumption needs. Rapid and extreme changes in water level height created unsteady ice conditions and made the river more difficult to use.

The changed landscape, loss of salmon, and highly regulated waters left many disconnected from the river and created voids in the space, culture, and biotic life of the watercourse. To produce electricity, the generators now rumble day and night, but the roaring of the old rapids, the chatter of past cultures, and the sounds of lost species are gone – today, the river Kemi is silenced.

Kemijoki offers an interesting setting to dive into the interrelations of the built and natural world, humans, and non-humans. By choosing a river as a site, this diploma aims to better understand the complexity of factors that shape the built environment and how ecosystems and landscapes are affected in the process.

HOW – by listening and researching

To better understand the vast landscape of Kemijoki and its complex dynamics, throughout this semester, I have entered the site from multiple directions, listening to and following the stories that resonated and spoke to me.

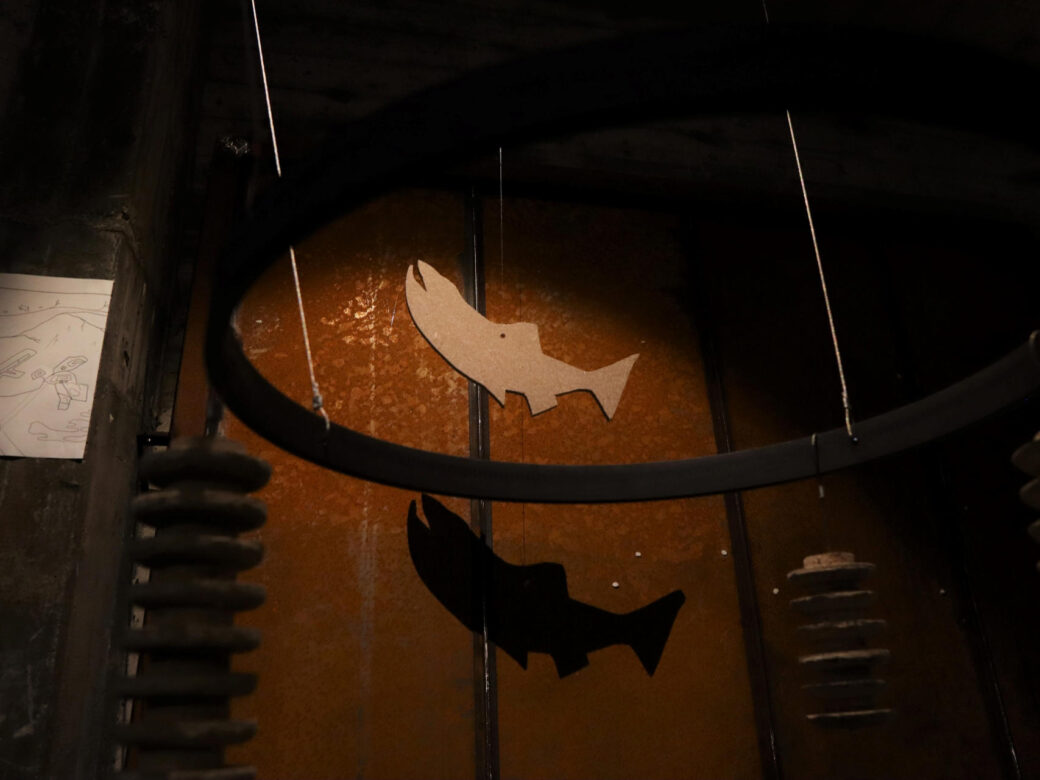

First, I started the diploma journey by reading and writing about rituals. Around the same time I was writing, I came across an annual protest along the river, Blessing of Sieriniemi, that opposes plans to build a new powerplant. I found the protest interesting, and in my essay, I ended up analyzing how the event could be understood as ritual behavior. From the protest, I found it especially fascinating how salmon as a symbol was used in the visual language of the protest and how in 5 years, it developed from representing loss and damage into a symbol of resistance and collective joy.

This, as my first entry to the river Kemi, I continued the diploma journey and, like salmon, traveled the river upstream, stopping at many of the hydropower sites. Over two weeks, I collected hydrophone recordings from under the ice of the river in order to explore what sound can tell about the present and what lies beneath the surface of the river. I also used sound and the act of fishing (sounds) as mediums to discuss with locals to better understand how people experience the river and to see what memories sounds can evoke.

Throughout the semester, I’ve also mapped and analyzed the river and its inhabitants. I’ve looked into the river’s past by analyzing river from its primary modes of extraction: fishing, timber, energy, (and mining). By analyzing the main industries, I’ve aimed to understand better how the extractive processes have shaped the river and what infrastructure they’ve produced. To ask how non-humans have been affected by the industries, I’ve also looked into some of the river’s endangered species: sand martin, blunt leaf sandwort, freshwater pearl mussel, and hydropsychidae. Studying the species, I’ve also aimed to broaden my views on the different ways of inhabiting the river and how the river and its inhabitants change according to seasons. By also seeing what qis data is available, I’ve tried to get an overview of the life and processes around the river.

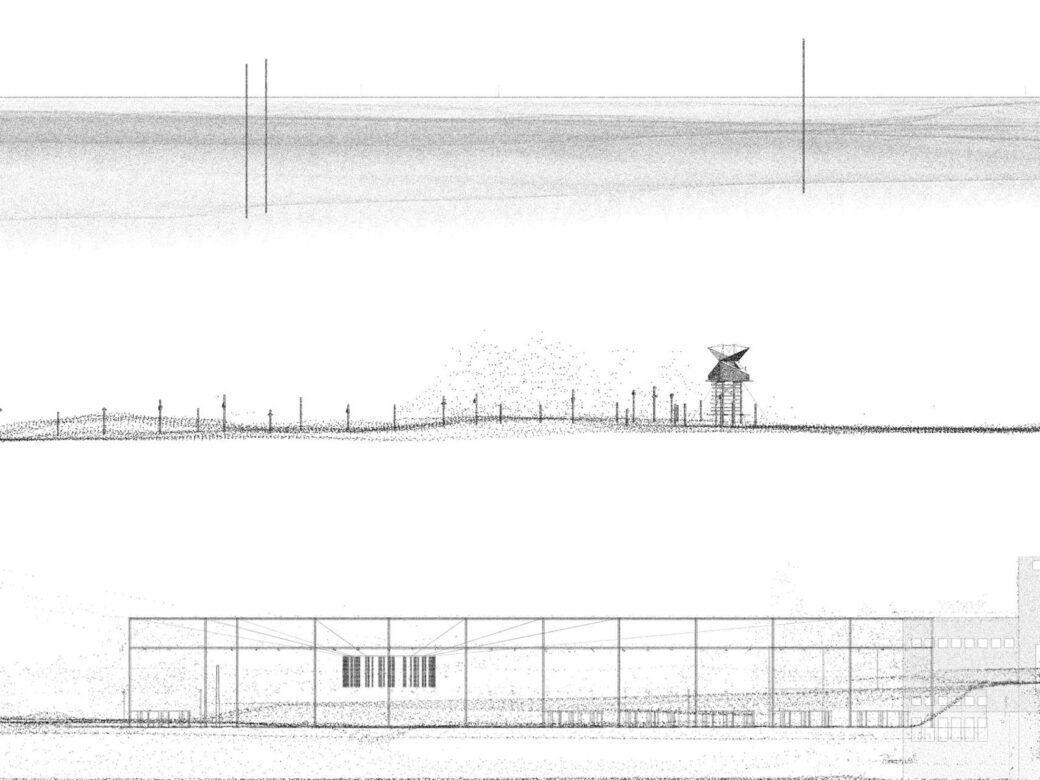

In addition to examining the river as an entity and as a result of the journey along the river, I’ve focused more deeply on three hydropower sites along the river: Isohaara (damscape), Pirttikoski (dryscape), and Porttipahta (floodscape). These sites I selected because they represent the landscape types most dramatically altered by hydropower and locate on different parts of the river, close to the start, middle, and end of the main branch, thus allowing a diversity of approaches for the final project.

WHAT – disruptions and echoes

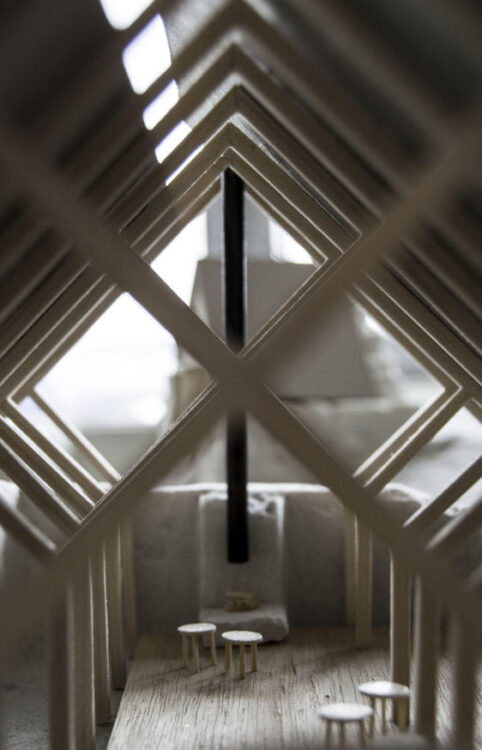

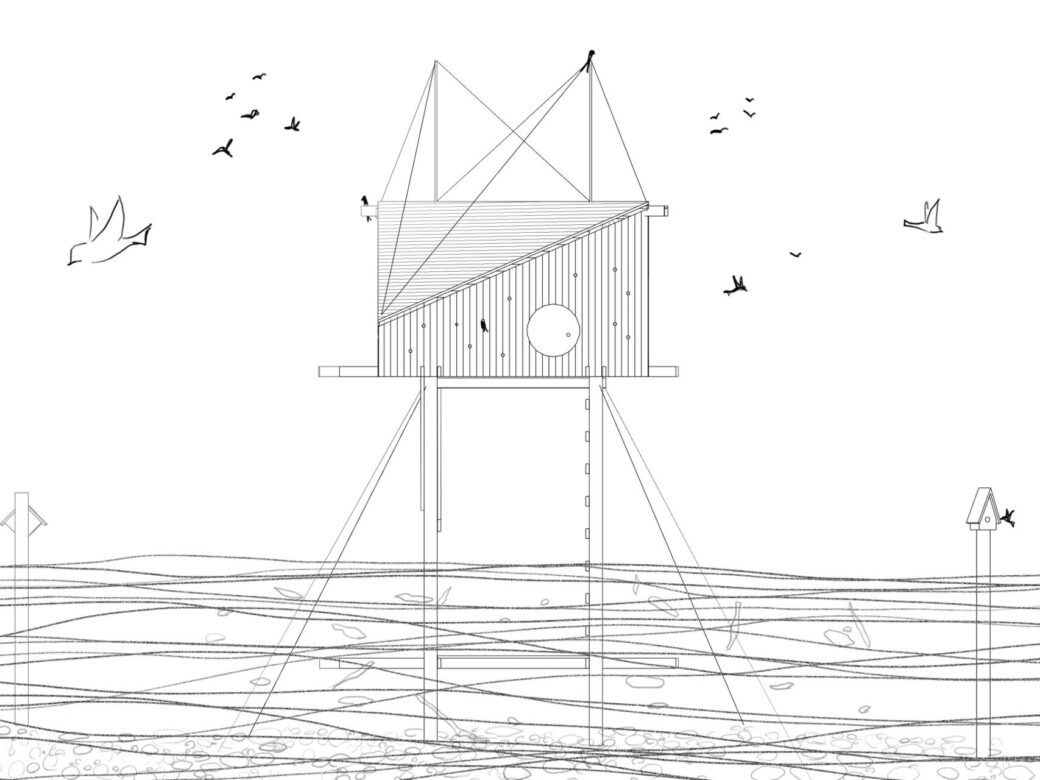

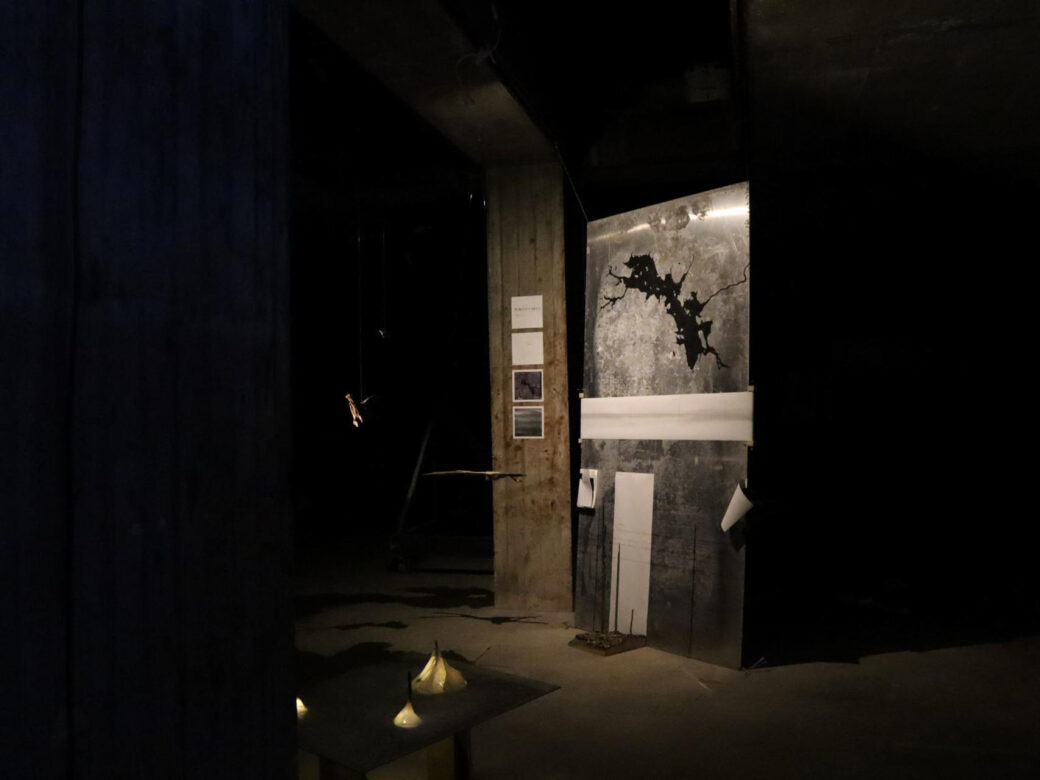

The final project consists of three interventions proposed for the three selected sites damscape, dryscape, and floodscape, and a website, an open archive of the research from this semester. The three interventions, constructed mainly from decommissioned electricity parts, draw from the research in order to explore the following questions:

• How to visualize and create awareness of past and current processes of extraction, their impact on the river and its various forms of life?

• How to understand, reanimate and promote various ways of living with, around, and within the river?

• How can the spatial and cultural erasure created by hydropower exploitation, the loss of salmon, and other extraction processes be digested, and its voids reactivated or filled in with new life?

• How to gain back a sense of ownership from the industries and hydropower?

• How could alternative architectures of/along the river encourage inclusivity and care, hosting and nurturing instead of focusing on control, domination, and extraction?

• How to change the perspective from the river as a resource to the river as a network of life?

• How to live and die well with the river and the life it supports?

• How to think like a river?

WHY – to sound

As humans struggle to free themselves from fossil fuels, the demand for sustainable energy is on the rise. In the Finnish context, Kemijoki is one of the major sites of ”green” energy production. It is the biggest single hydropower producer site and the only place where a new hydropower plant is still being planned. Mineral searching for technologies and bioindustries are also increasingly present in the river basin and pose new challenges for life below and above water.

In a world with increasing demand for green energy, the history of Kemijoki raises important and critical questions about the production of energy. Is it environmentally sustainable if energy production leads to the extinction of a species’ ecotype? Is it socially sustainable if hundreds of people and animals lose their homes for it? Is it economically sustainable if positive economic effects for the locals are only temporary?

Alternative forms of energy are needed in order to get rid of fossil fuels. But most likely also a reorganization of life and coexistence that turns to less energy-avid dynamics. So-called green energy is a response to the energy crisis that is primarily focused on producing more energy otherwise. A similar approach is often followed within the building industry, and the architectural profession, where building more is usually the prevailing ’mantra’.

I believe it is important to develop alternatives to these dominant discourses and practices, and instead of always proposing ’more’, carefully investigating the possibilities of a ’lesser’ mode, focusing and shining light on the ’how’.

The diploma project has therefore been a journey to investigate the potential of architecture as a tool to explore and address bigs issues such as energy production and extractive practices, but also modalities of memory, remembrance, mourning rituals, spatial and cultural healing, coexistence, and life, as sites and threads of intervention for engaged and inclusive architectural practices.

For further information: https://soundingsilence.cargo.site/