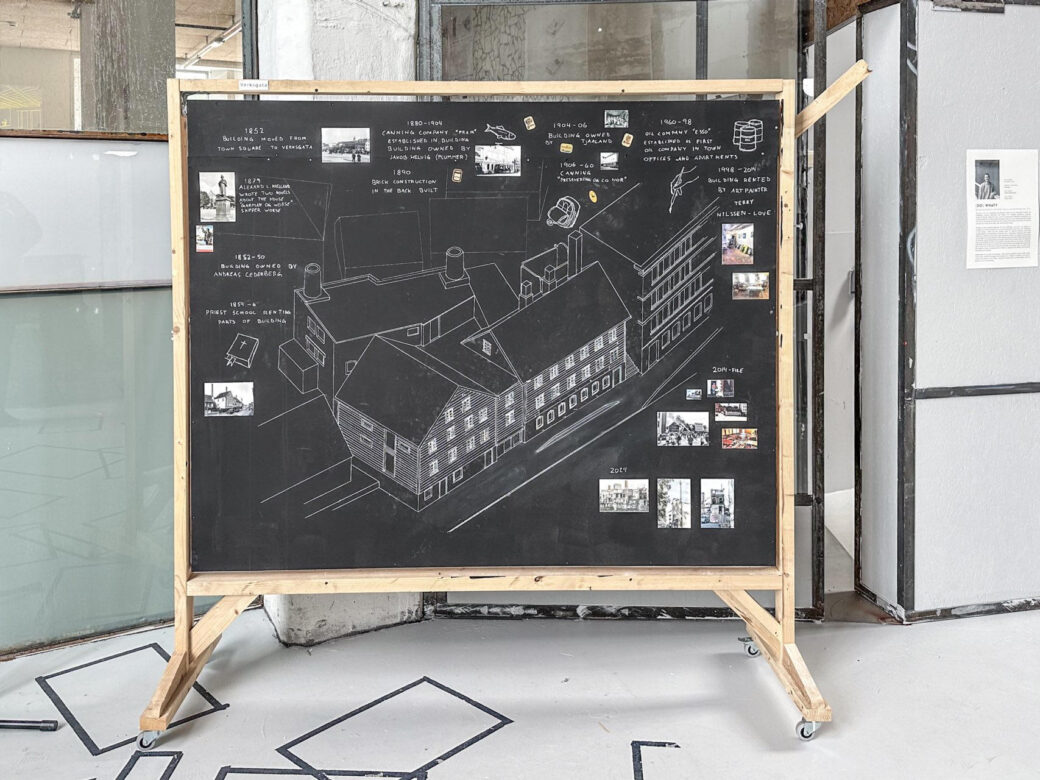

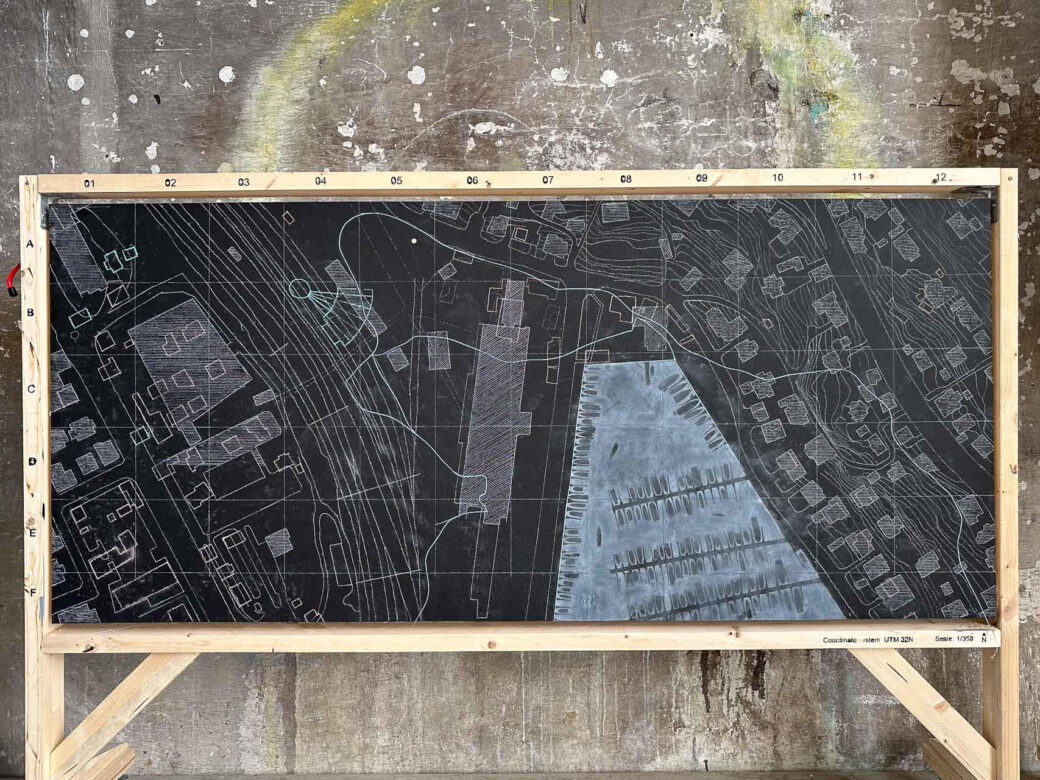

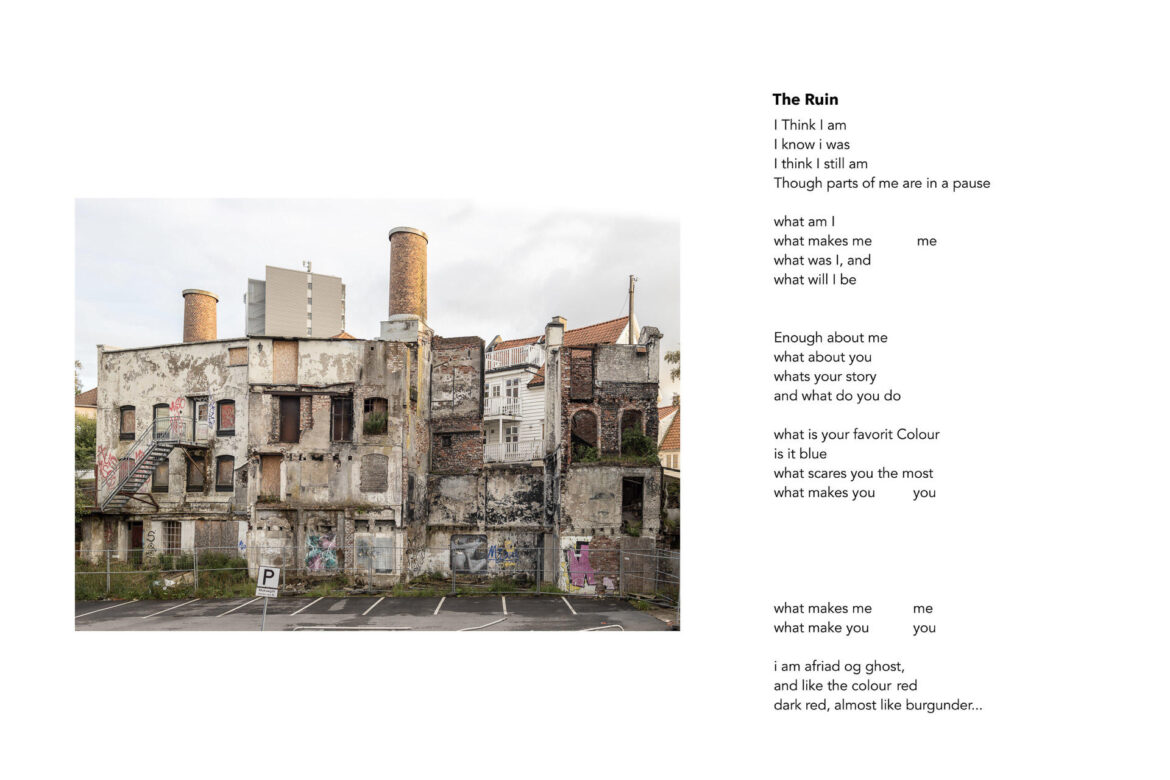

This project delve into the complex layers of collective memory, and urban transformation, by examining two specific sites in Stavanger: Verksgata and Paradis. Both rich in memories and on the cusp of significant change. Stavanger currently stands on the edge of an urban dilemma. With rapid population growth and the pressing need for housing. Large developments emerging within the city center, where old industrial sites and buildings becomes focal points, primarily driven by real estate companies with profit motives. Spaces ‘rustling’ with activity. This project does not seek to halt the wheels of urban development but rather to question and reframe the narratives that guide such change.

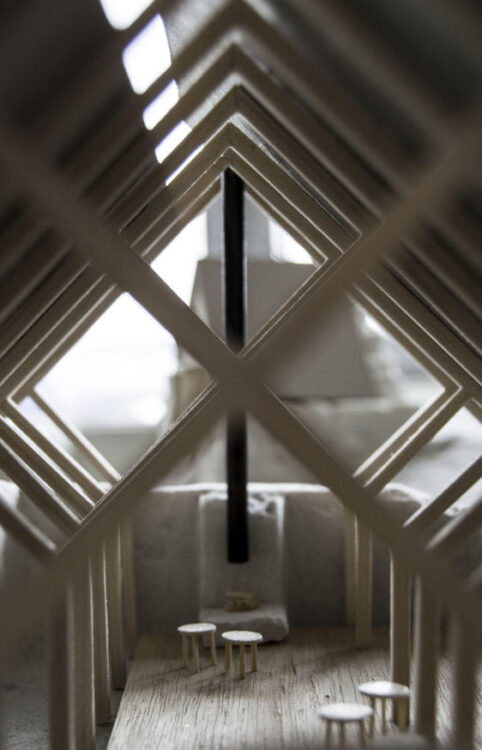

Additionally, the project incorporates a third site, the cathedral space at BAS, where i have been working throughout the semester as a reflective workspace that have allowed me to apply my learnings from Stavanger to the cathedral itself, and vice versa.

“Time present and time past are both perhaps present in time future, and time future contained in time past.” (Eliot, 1943)

Drawing inspiration from T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, this work reflect on time as a continuum and therefore the question extends beyond merely what we preserve from the past and what we aim for in the future, but how we understand the city as part of a continuous steam — here, now.

“What might have been and what has been point to one end, which is always present,” (Eliot, 1943)

How do we safeguard our environment as part of an ongoing narrative? Can the past and future inform the present? How do past and present look forwards?

The transformation of industrial areas into new entities often reflects broader economic and political trends, where luxury residences rise along the waterfront, tilting towards a market-driven model that risk sidelining considerations of what Henri Lefevre describes as “the urban.”

“Lefebvre speaks about the struggle between exchange value and use value, between the city as site of accumulation and the city as inhabited. The industrial capitalist city that we experience every day, he believes, is given over to exchange value. What he calls “the urban,” on the other hand, nurtures use value and the needs of inhabitants (1996, pp. 67–68). It is a space for encounter, connection, play, learning, difference, surprise, and novelty.” (Purcell, 2014, pp. 149)

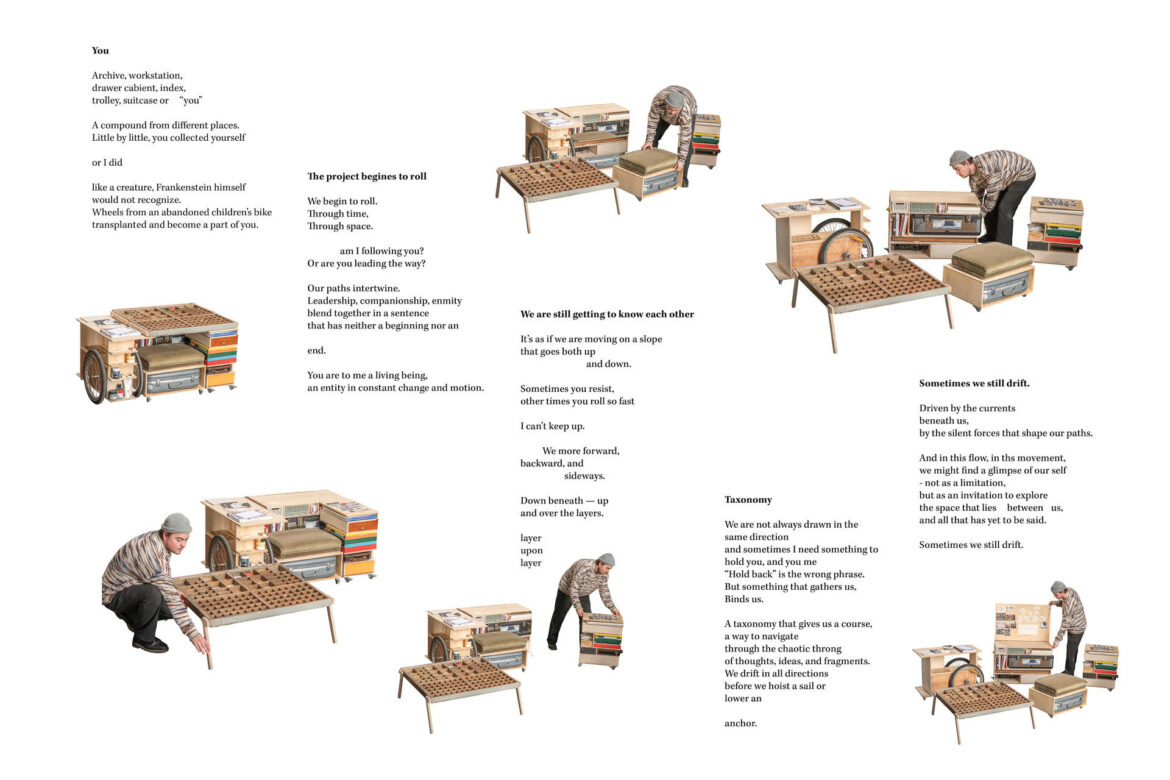

This project seeks to engage these sites not just as locations of change but how the presence of other stories can open up for new ones. By recognising these places and moments not merely as remnants of the past, but as spaces that hold seeds of unrealized meaning that can spontaneously emerge, this project suggest a shift towards a city that values encounters, awakenings and the experience of a more shared form of urban — a city full of urban flowers. For what is a suitcase, if not a temporary home for what we value most? And what is a city, if not a suitcase shared by us all?

In this entropic mix of narratives across time, how do we distinguish what is relevant and useful?—today, tomorrow? In Stavanger, I collected stories and feelings tethered to these places from people that i met. And what matters to them I unconditionally wrote down. These are observations that in various ways demonstrate this precarious balance between what might hold meaning and what might be seemingly inconsequential detail.

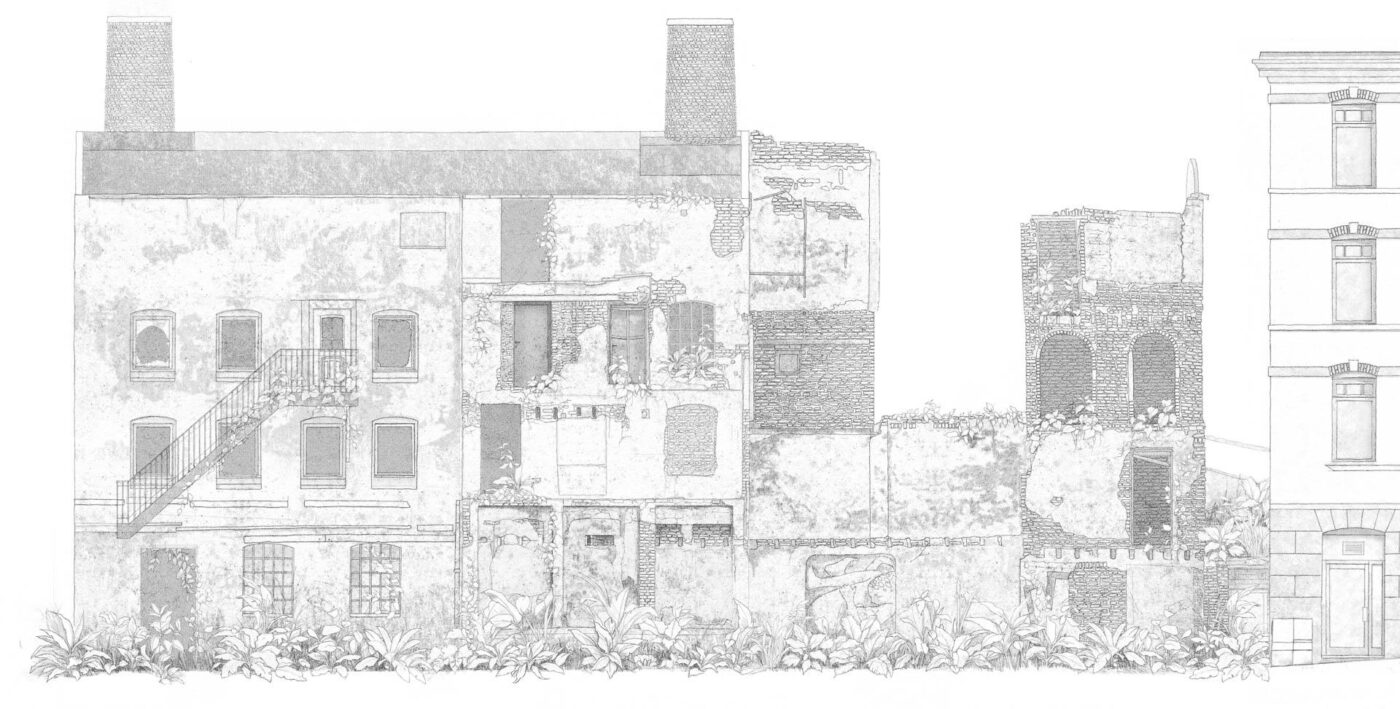

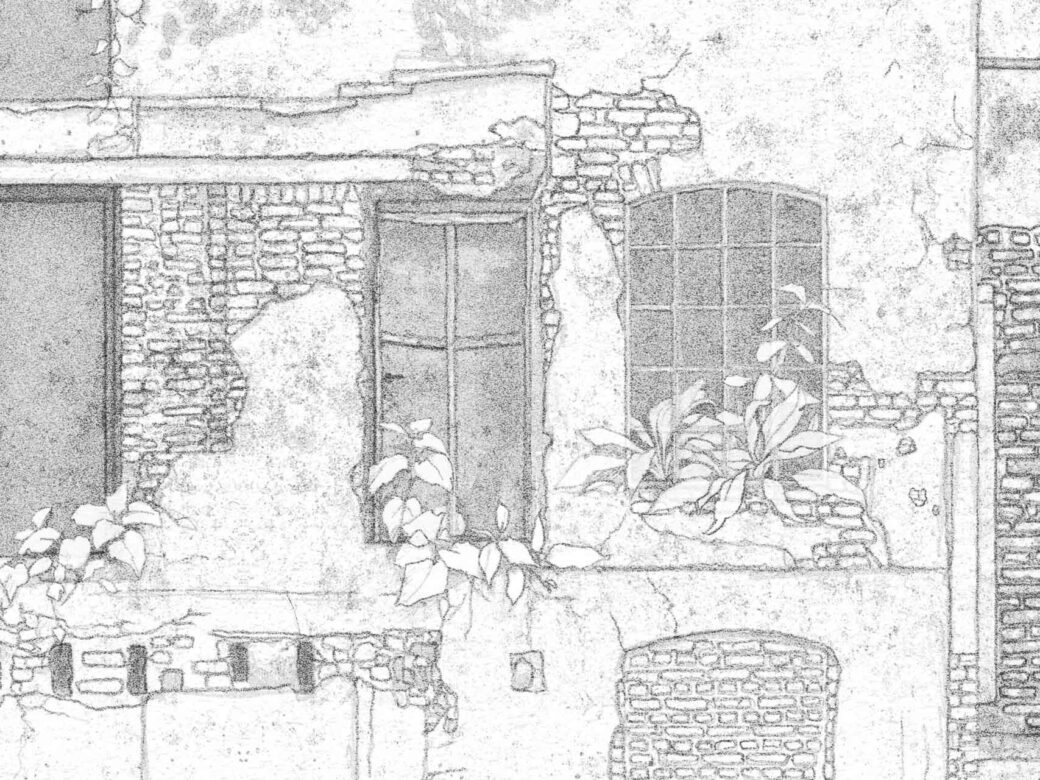

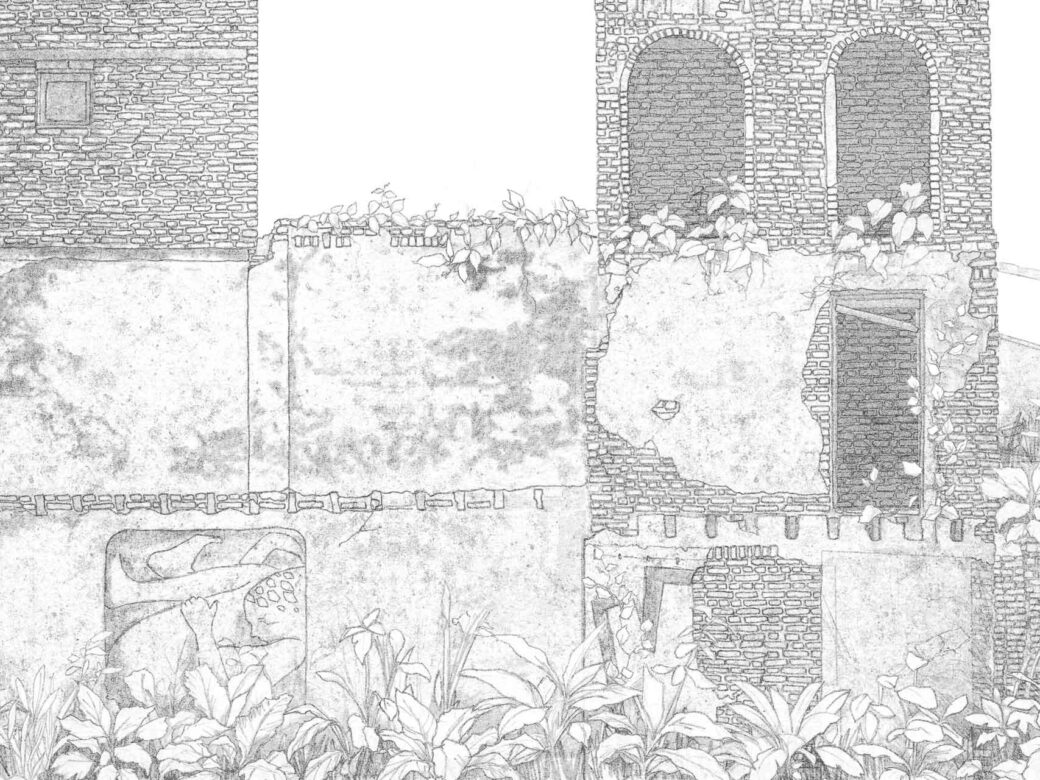

An old porcelain ashtray attached to the wall in one of the toilets, door-labels beckoning one into spaces that no longer exist, An old opening hours sign with small, yellowed plastic letters neatly tucked behind glass, in tiny, narrow grooves. These small details fill every nook and cranny of the goods terminal in Paradis. Details that do not seem directly part of the immediate narrative of the place. How important are these elements today, or how redundant? Do they contribute to a greater understanding of the past? Are they waiting to be given a meaning, are they small fragments without any direction, matter lacking any value?

Roland Barthes introduces the concept of “the reality effect’, where he suggests that the purpose of superfluous elements in a story, those that never acquire a function and fail to connect with the narrative – are meaningless? – and there only purpose is to represent the real and paradoxically reinforce the narrative. And so in this sense, narrative – logic -sense, is dream and the real is meaningless and in want of its dream.

If we look at these spaces as stories—stories we enter, live within, both read and write, these elements interruptions, distractions, portals, do not directly lead us anywhere, but conjure an invitation to follow somewhere – to see them as something that can acquire meaning or something that remains just an ordinary object.

Eliot talks about the “still point of the turning world,” where there is neither movement from nor towards, and “there is only the dance.” Amidst constant change (social, architectural, commercial), there are still points, moments, places, and memories that can matter.

What becomes the architect’s role in this? Positioned at the intersection of market forces, inhabitants, and the urban fabric itself. By understanding these moments, or attempting to understand their potentials — through reading them, being in them— we can mediate these forces, acknowledge the illegible and safeguard what might be flourishing of the urban.