Intention

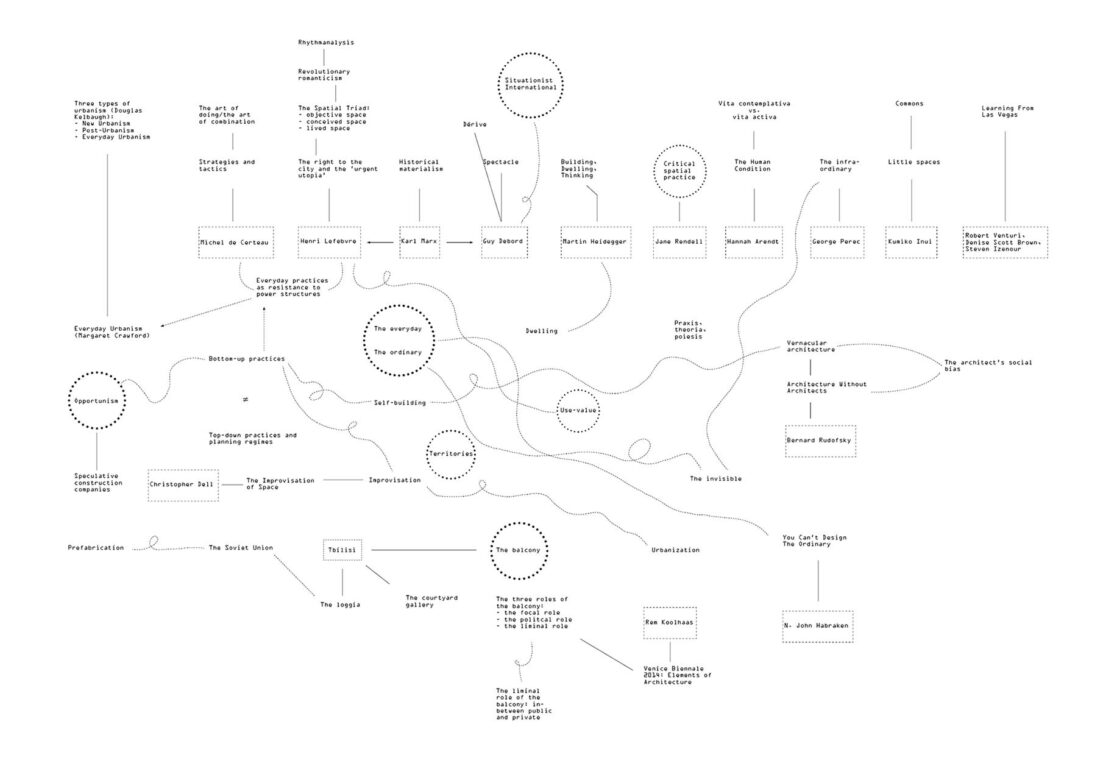

The project is an exploration of the concept of ’everyday life’, by looking at architectures that are generally overlooked within professional discourses. It is a reflexive and tactical search for a method, as well as a personal search for a critical stance.

Tbilisi and the protagonist

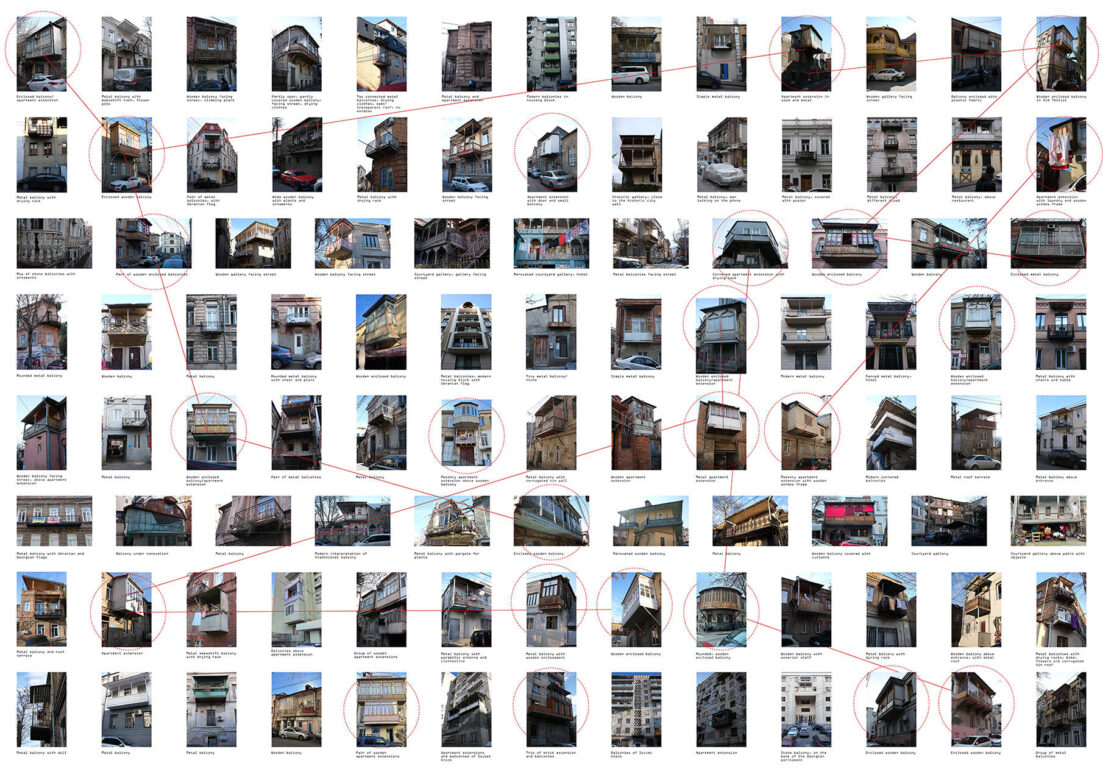

Inspired by Henri Lefebvre’s and Michel de Certeau’s theories on space and everyday life as critical political constructs, the project takes form as a practice-based research of Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia. There the project started as a fieldwork, based on the hypothesis that everyday nuances are more easily recognized in a foreign context. The city’s liminal position in the global east-west dichotomy makes it an interesting case in the study of everyday practices within changing planning regimes. To navigate I chose to follow the balcony (and typologically related building extensions) as an architectural protagonist.

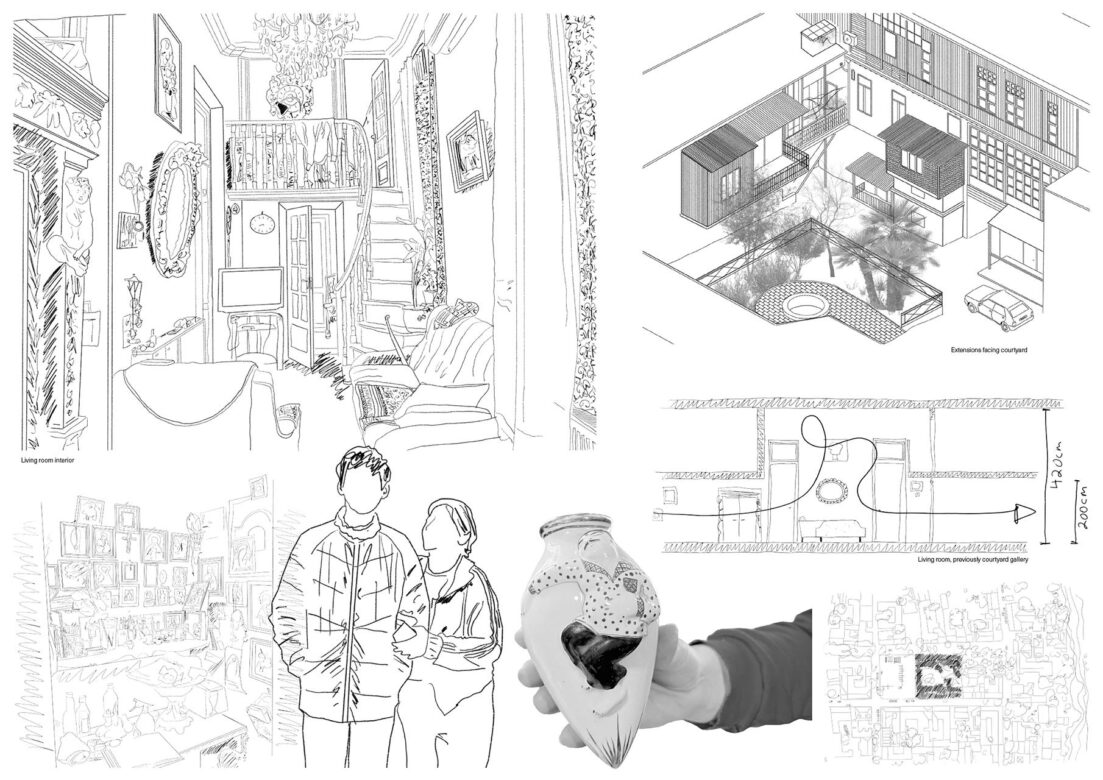

The study of Tbilisi has been two-sided. On the one hand I studied the city horizontally. By navigating categories of balconies I aimed to get an overview of historical planning regimes to better understand recent and current cultural narratives. On the other hand I decided on certain architectures to study vertically. This was done through a set of qualitative studies of interior spaces: the protagonist as seen from the inside.

As balconies are situated on thresholds between territorial spheres, they are carrying testimonies of the human territorial nature. Political instability, social injustice, as well as influence by rural culture have led to a rise in informal practices in Tbilisi. This includes appropriation of space and spatial organization beyond formal boundaries. The territorial tensions of the Tbilisian liminal architectures illustrate the meaning of space as socially contested.

Towards a method

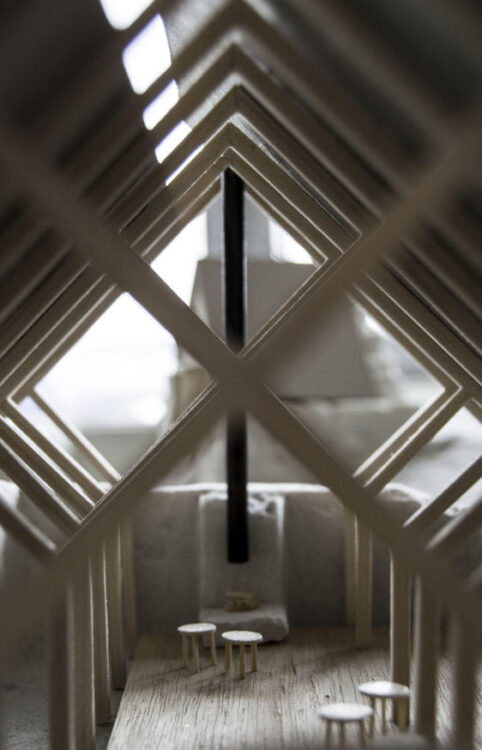

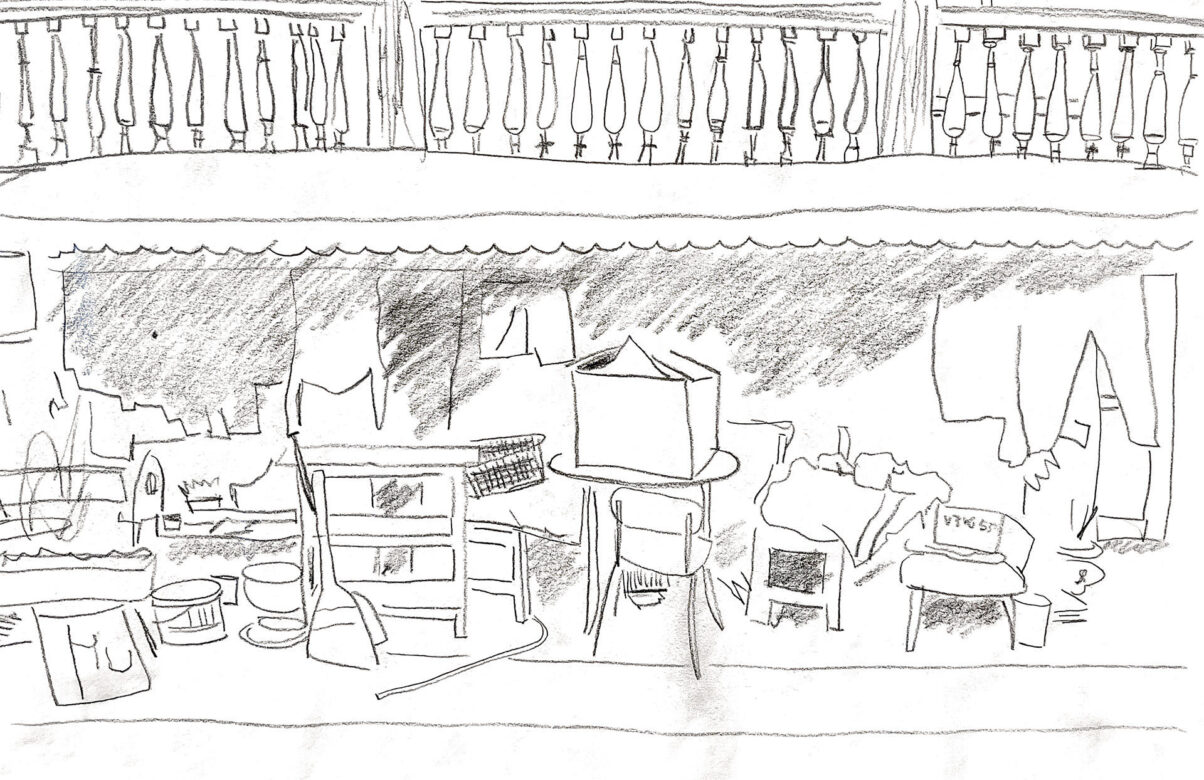

During the second part of my project I started working in parallel in a physical space at Bergen School of Architecture, with the aim to embody my research, acknowledging that architecture starts with the body and that the everyday exists in the scale of 1:1. The goal of the laboratory was to practically reflect on knowledge from the previous phase and eventually formulate a set of methodological principles. Among them most importantly stands to practice tactical thinking and to nurture use value: to cultivate the usability of space.

Henri Lefebvre encouraged “a style of thinking turned toward the possible in all areas”.[3] To recognize architecture as culture means to see that space is culturally produced. This suggests to challenge cultural conventions as a method towards positive change.

References

[1] Upton, Dell (1968) Architecture in Everyday Life New Literary History, Volume 33, Number 4, Autumn 2002, pp. 707

[2] Ibid. pp.712

[3] Lefebvre, Henri (2009). State, space, world: Selected essays (N. Brenner & S. Elden, Eds; G. Moore, N. Brenner, & S. Elden, Trans.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp.288

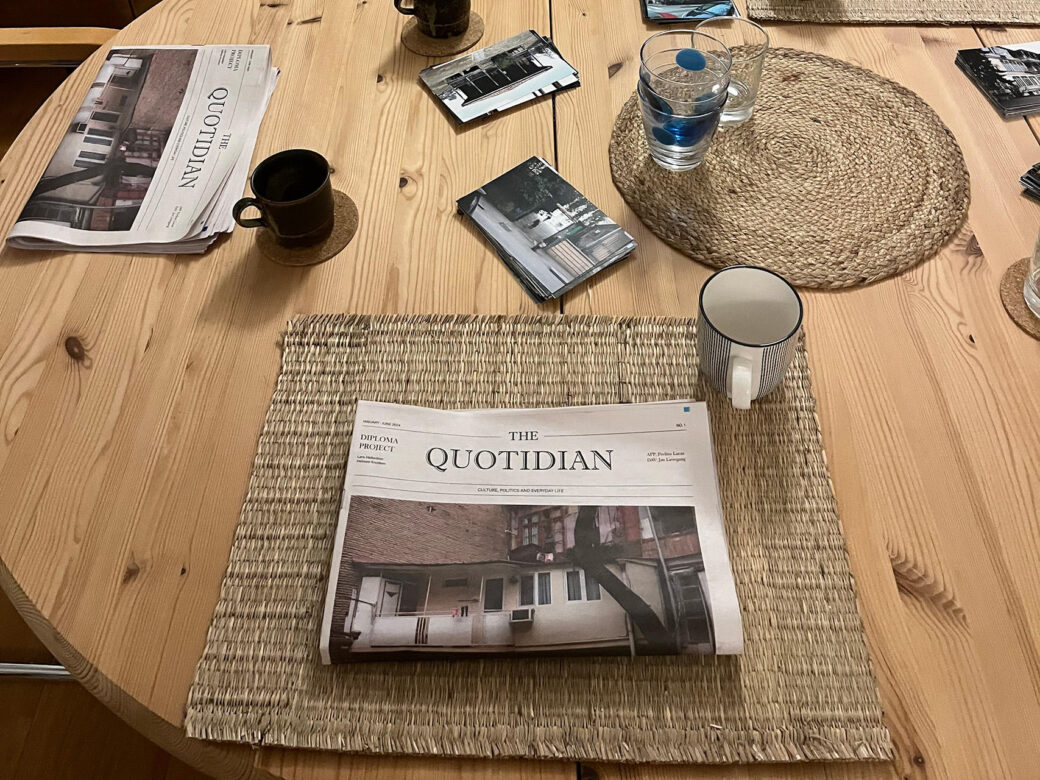

My exam presentation was held around the kitchen table in my own home Saturday 29th of June 2024.