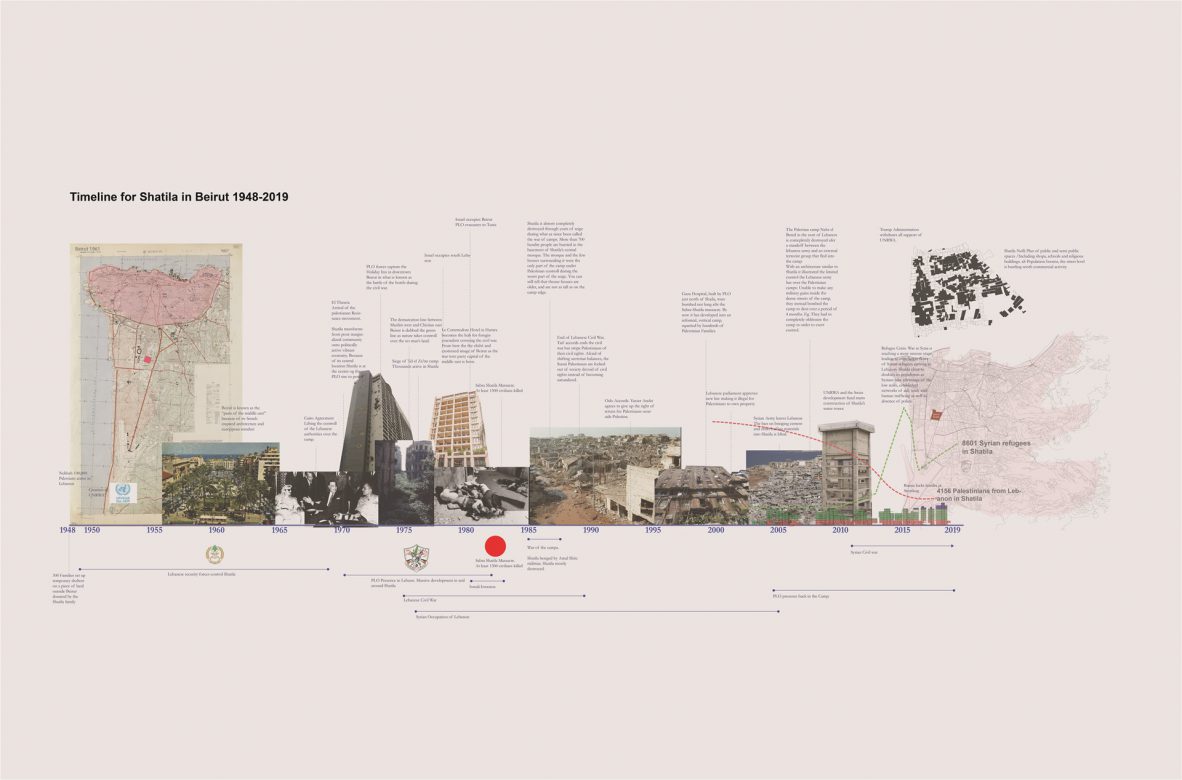

Except human lives are never on hold. Time passes, lives unfold, and experiences are lived. Rows of tents become concrete towers filled with homes. The temporality embodied in the term camp, prevents us from recognizing the placemaking that happens when humans live their life in a physical environment. The stories and systems propagated by journalists, NGOs, UN agencies tell a story of constant crisis, one that robs people of dignity, and leads to an endless cycle of either failing or inefficient aid development projects.

Because it is so centrally located in the city that functions as the hub for western foreign correspondence, aid and diplomacy for the middle east, Shatila has become the poster child of the refugee crisis. In the constant reproduction as the backdrop for stories of misery and desperation there is no space for the portrayal of a complex urban area that in certain respects can be said to function as Beirut’s actual centre.

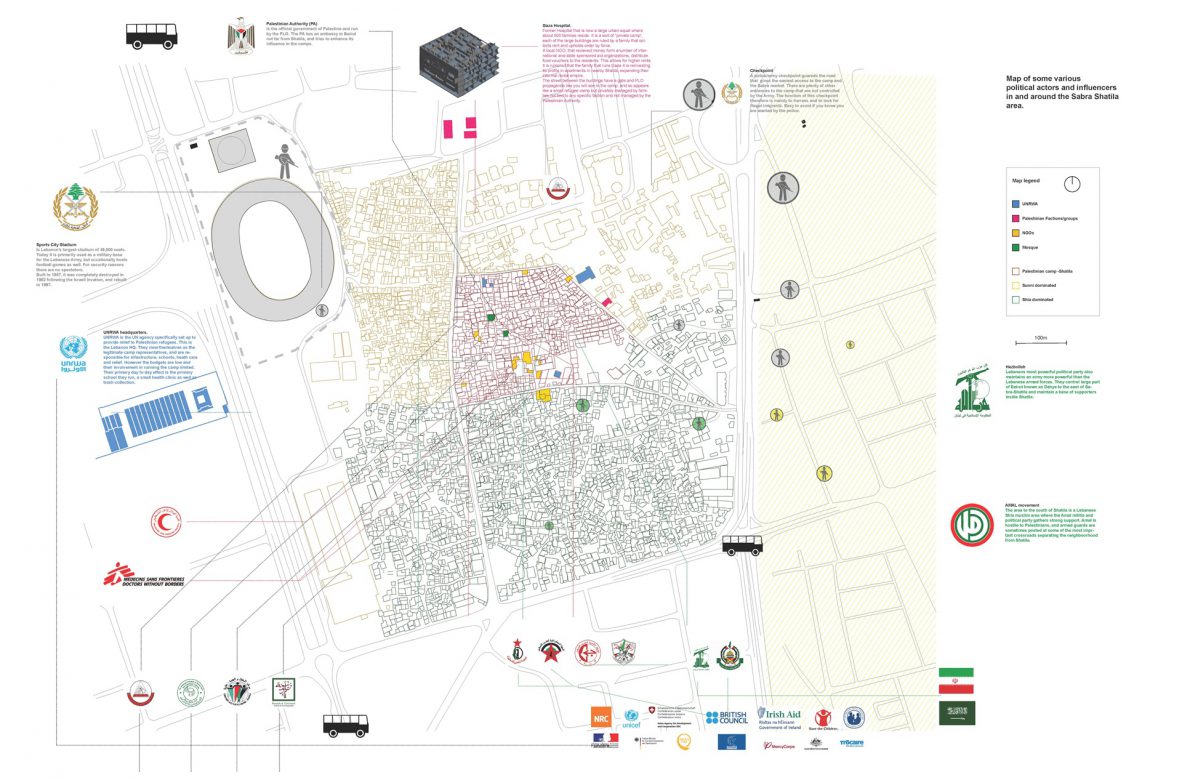

This project engages in an architectural anthropology, explores the logic of its built environment, attempts to map and draw the spaces created by the population of Shatila over the past 70 years seriously, as well as analyses its place within the city. Furthermore, the project try to critically explore the relationship of outside NGOs, researchers and audiences have to urban development of the camp.

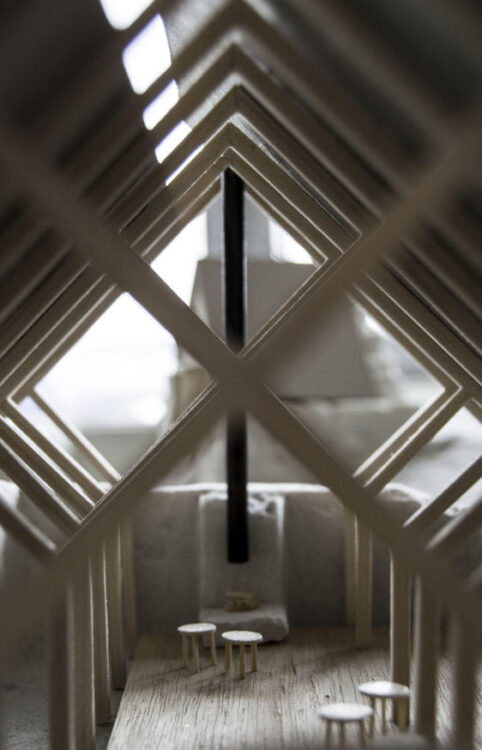

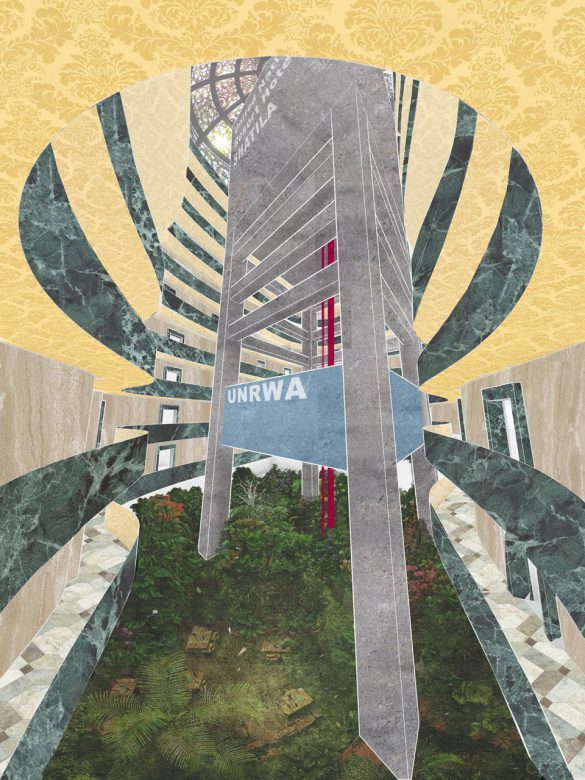

I am proposing a hotel on the site of a defunct water tower, another international aid project to that failed because of poor knowledge of local context. The hotel will be a United Nations – private sector joint venture, attempting to bypass the dysfunctional and gridlocked politics, in an attempt to revive the failed project. The hotel will host the international aid workers, journalists, researchers, language students, political sympathisers and so on. Needing water, the hotel will run the pumps and desalination systems already installed in the water tower, and as a by product will provide water to the rest of the refugee camp too.

Constructed using local techniques and labour, by buying services from businesses in the camp and selling a highly refined product that invites the visitors to leave as much money as possible inside the camp ecosystem, the hotel promises a new form of sustainable market driven development.

Hotels are sites with complex geopolitical functions; Islands that provide a sense of normality during war, neutral ground in which to meet, spaces for both transparent and shady transactions, as well as sites for neutral leisure and containers for projecting dreams. Tourism is a popular, but also very controversial tool for development as there is a whole set of issues that comes with it. The architecture of the hotel becomes a model of the camp, its relationship to the outside, and a to question the ethical practices of aid work.